Building #24

Factories and skyscrapers

I gave a talk yesterday at a university conference about an interesting aspect of my recently submitted doctoral thesis on the history of buildings.

The focus of the talk was on factories and skyscrapers in the USA.

Factories had been around since before the First Industrial Revolution in Britain, at least in a proto form in the 18th century, and then more like the ‘dark satanic mills’ subsequently all round the globe.

Skyscrapers started in Chicago towards the end of the 19th century as the response to a major fire in the city that had devastated timber-based construction. Architects then turned to steel, previously reserved for the North American railway network, as an economic means of building high in a limited plot size. I posted about a skyscraper under Building #4.

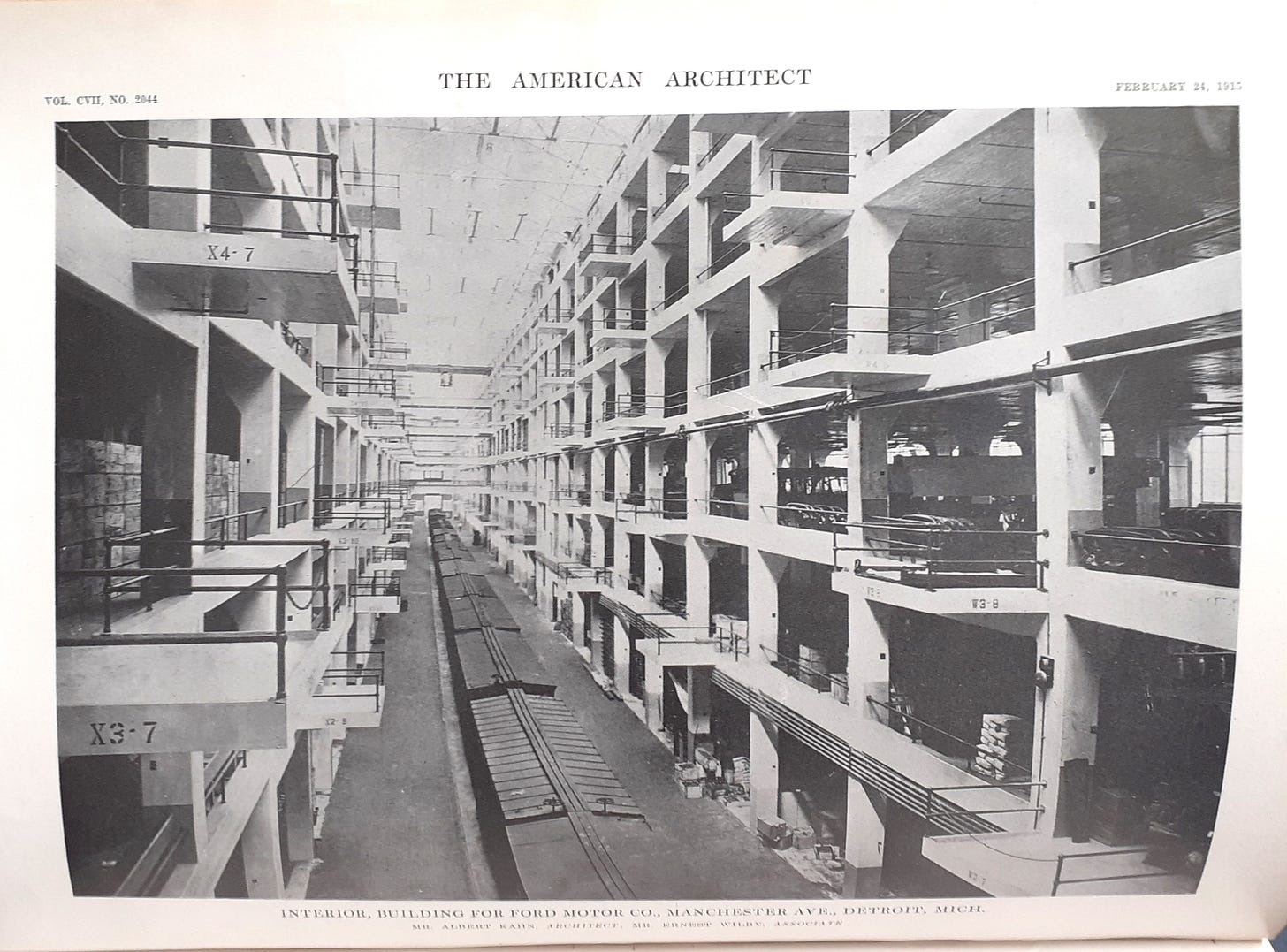

The relationship between these two types of building became more closely aligned with the construction of ‘daylight factories’ at the start of the 20th century in North America. These were large factories built using reinforced concrete skeletons and with significant glazing to allow more natural light inside. The epitome of the genre was Henry Ford’s vast and expandingModel-T car factory outside Detroit, started in 1912 (see below). I first posted about this place and another ‘daylight factory’ under Building #7.

Trains would bring in the components on the ground floor and they would be hauled up to galleries on the other levels, from whence they could be distributed to the assembly line. The manufacturing process was highly rationalised, in order to speed production up and so maximise economies of scale.

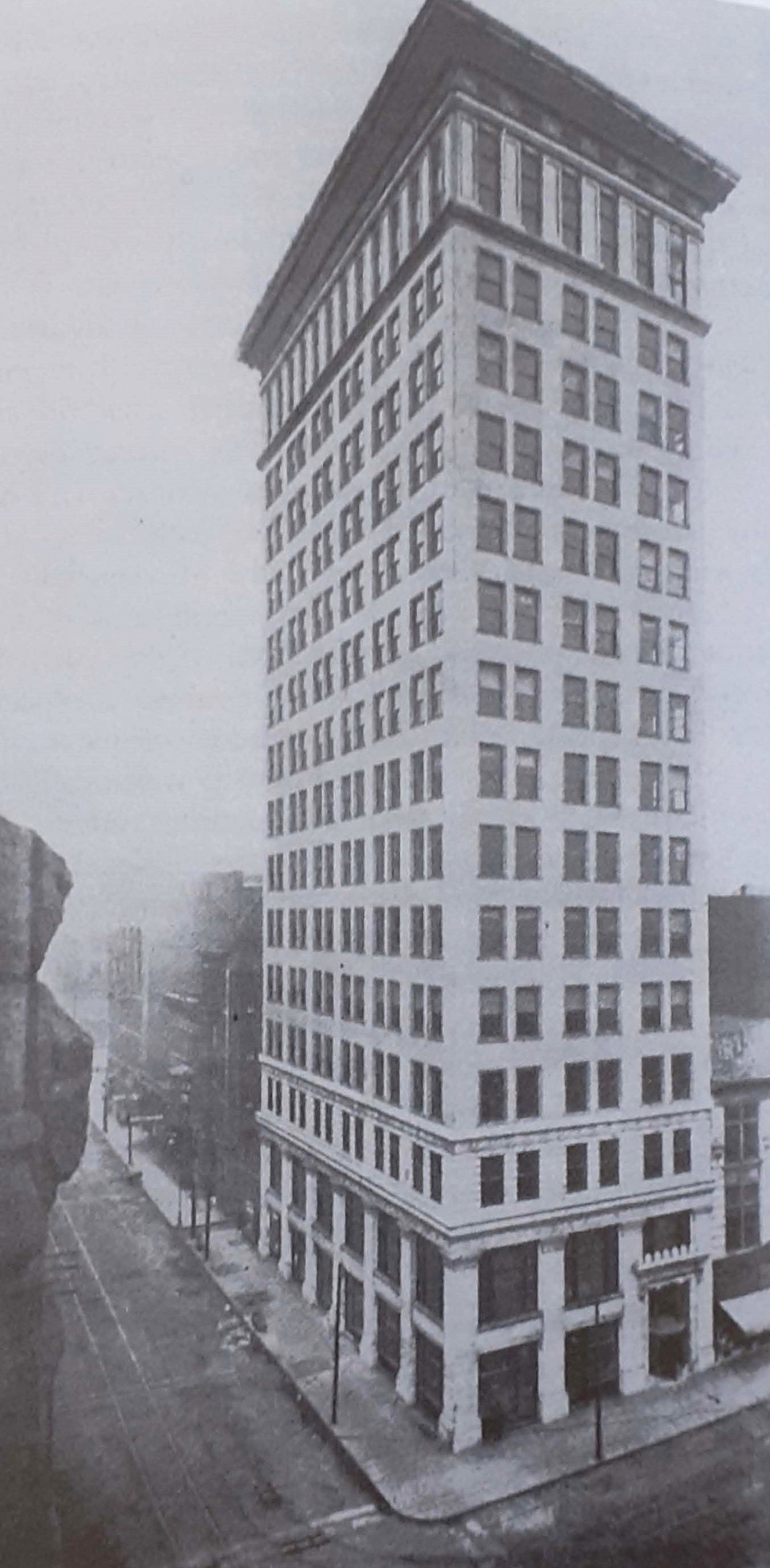

‘Daylight factories’ had precedents in highly glazed industrial buildings also constructed using reinforced concrete found in Northern France and Belgium before the First World War. But they also connected to the original Chicago skyscrapers - in 1903 the first reinforced concrete skyscraper was completed in Cincinnati (see below).

It is possible to argue that Ford’s factory was a horizontal version of the earlier Cincinnati skyscraper. The same principles applied to both buildings, in that as much natural light as possible needed to enter through the extensive glazing. This was not an unusual approach to construction and indeed the first major building to use glass panels on a very large scale was the Crystal Palace in London, completed for the 1851 Great Exhibition. This was soon followed by new types of highly glazed buildings such as railways stations, shopping galleries and department stores.

‘Daylight factories’ became a model for International Modernist approaches to plainer, geometric, industrial architecture after the First World War, exemplified in works by Le Corbusier and Gropius. I will expand on this in a subsequent post.